As we saw in Part 2, deliberate practice means nothing more than to practice with purpose and a specific direction. This term and area of research was pioneered by researcher K. Anders Ericsson and was the first major change-up in common thought regarding what develops skills to world class status.

Ericsson also concluded through years of observation of world class performers, artisans, musicians and chess masters that 10,000 hours of deliberate practice was needed to achieve a world class status in any given skill.

10,000 Hours and the Society-Wide Game of Telephone

While Ericsson’s work is certainly revolutionary in the field of skill development, his work has been subjugated to a society-wide game of Telephone. For those who are unfamiliar with the game, one person in a group begins by whispering a phrase into one player’s ear. The listener then has to whisper to the next person what they think the first person said. The end result of the game is usually that the final form of the phrase is nothing at all like the original.

As Joshua Kaufman points out in a very popular TED talk, Ericsson’s work underwent a similar transformation since it was first unveiled to the public: his 10,000 hours premise as a baseline for achieving expert status in a given skill has instead evolved into being a baseline for achieving a basic level of skill.

In this article, in addition to understanding Ericsson’s 10,000 hours premise and how it’s evolved, we’ll also examine how one other researcher believes that basic skill development can be achieved in just 20 hours.

“The First 20 Hours” and the Difference Between Good Enough and Expert

Kaufman formally challenged Ericsson’s work with the book, The First 20 Hours, arguing that though it does take a lot of time to become an expert or a world-class performer at any given skill, it doesn’t take 10,000 hours to get good enough at a skill.

Rather, his position is that it takes about 20 hours, or a month of practice for 20-30 minutes a day (with roughly 2 to 3 missed days), to get ‘good’ at a skill.

Kaufman describes being ‘good enough at a skill’ as being skilled enough to think independently about a skill and self-correct. Of course, ‘good enough’ is very subjective. To some, good enough might mean knowing enough guitar to learn some Beatles songs and perform them for friends. Others might define it as being able to perform intricate solos and develop their own solos heavily rooted in the application of music theory.

In contrast to being ‘good enough,’ an expert “not only acquire[s] content knowledge as they practice cognitive skills, they also develop mechanisms that enable them to use a large and familiar knowledge base efficiently”. This takes more time, but reaching a good level of skill development sets the student up for additional progress.

What Can Teachers Take Away From Kaufman’s Findings?

While all teachers want their students to go far musically and not just stop at good, the bigger thing to realize here is that Kaufman provides a very actionable, practical framework for teachers to follow — especially when teaching students who are brand new to their instrument.

Kaufman argues that all teachers need to do is:

- Deconstruct the skill or break the skill down to its most fundamental components. For some music students, you may want to focus solely on learning proper form, some basic scales and a song or two.

- Help students self-correct or learn enough to identify what is right, what is wrong and how to learn from these mistakes effectively.

- Remove barriers to learning by removing all distractions. Focus should be entirely on the instrument itself and not something else.

- Practice at least 20 hours – or 20-30 minute sessions daily.

Think about providing the student with enough context, information, and insight so they can go home, practice and, most importantly, self-correct themselves. This approach also leaves enough room for the student to use what they’ve learned to pursue their interests independently, all while using the teacher as a resource to check their work.

For example, let’s say a student wanted to play guitar to learn Led Zeppelin songs on guitar. The teacher can begin by providing instrument basics, an introduction to major and minor chords, how to read tab and how to strum. This would allow the student to go off on their own and learn the Zeppelin songs they wanted to learn and return to their teacher to check their progress and develop technique.

The teacher now can toggle between being the teacher to the facilitator of the learning process – the latter being a role that too many teachers neglect.

Conclusion

Practice is a necessary aspect of any kind of skill development, but it doesn’t need to be a burden for the student to do or for the teacher to assign.

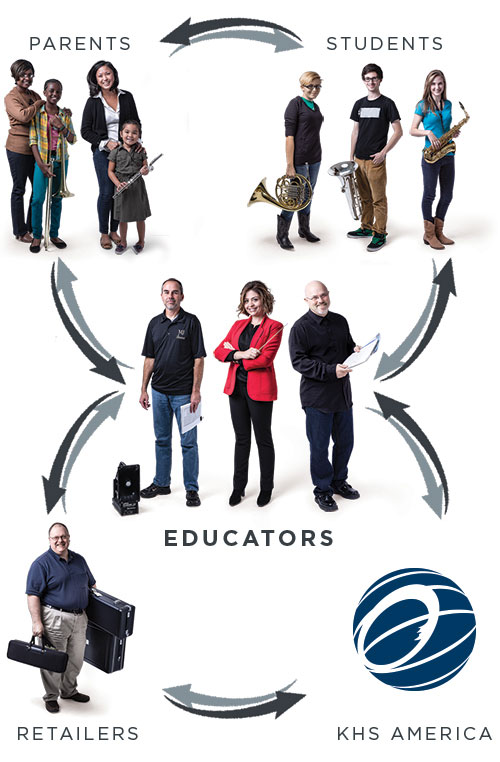

Recent academic research encourages us to move away from the outdated student-teacher relationship model, where the teacher assigns certain passages and songs and assumes progress will be made by repetition. Instead, let’s create a new model of skill development, a two-way street where the teacher and student work in tandem to develop the skill together!

Think about providing helpful, specific, actionable, and sustainable insights to students, giving them the tools and understanding they need to practice effectively. In turn, your empowered student, who knows exactly how to make the most of their practice time, can engage with the material and work critically to further skill development before your next lesson together.

About the Author

MIKE EMILIANI is a bass player, composer, producer and writer. He’s the editor and founder of Smart Bass Guitar, an online resource exploring bass guitar through long form instructional content, opinion pieces and expert interviews.Since elementary school, Mike has been musically active, beginning with trombone in 4th grade and later adding bass guitar and production software in high school to his skill set.Mike is currently the bassist for the live hip hop band Big Scythe and Soldiers of Life and the folk band Straw Man Standing. Mike also plays solo shows around Rhode Island and New England as 10 Volt Army, a one man band project combining bass guitar and electronic music. All the projects are based out of Rhode Island.

The content of this Blog article or Banded Story is the intellectual property of the author(s) and cannot be duplicated without the permission of KHS America and/or the author(s). Standard copyright rules apply.

We look forward to the evolution of this exciting program, and welcome feedback on how we can further enhance the work that you do in music education.

We are excited to offer your program the opportunity to join the KHS America Academic Alliance today.

We look forward to the evolution of this exciting program, and welcome feedback on how we can further enhance the work that you do in music education.

We are excited to offer your program the opportunity to join the KHS America Academic Alliance today.