In our lives, we thrill in finding the answers to mysteries, solving riddles, or discovering secrets. Teaching students to be sensitive and accurate with pitch and intonation can be an enigma, too.

The secret is… there is NO secret!

Developing performance technique occurs with a programmed approach, practice, consistency, and patience. Sightreading improves by doing it again and again! Development of a characteristic tone quality involves embouchure development, breath control, and long tone studies, to name a few.

In our field, we must face, perhaps, our greatest musical mystery. How do we approach intonation training?

Intonation Training

Teaching students and helping them develop an ability to discern small pitch differentiations must take a disciplined approach. It’s a requisite skill. Even the untrained can detect “out of tune” during performances. Like other performance practices, intonation training is absolutely a part of music education, and it, too, is a life-long skill. Let’s look at the process in a step-by-step manner:

- REFERENCE A reference pitch must be established. We are familiar with the solo oboist playing a pitch for a professional orchestra. The note is sounded. The winds play it back. The strings tune their instruments, and it’s magic.

The reference pitch must be checked for accuracy. Consistency is mandatory. Whether we tune with one other instrument or an entire ensemble, we must have a reference pitch. It is the standard to which we compare.

- INTERNALIZE The musicians must internalize the reference pitch. While the professional orchestra can create magic with their tuning, even they are internalizing the pitch. Young musicians should be encouraged to sing or hum the pitch. It must be absorbed so the pitch is heard in the head. They need time to listen and hum the note. Some might find it helpful to hold one ear closed with a single finger.

- ADJUST Finally, the instrumentalists must make adjustments to their instruments. After determining whether they are above or below the reference, the instrument needs to be lengthened or shortened to compensate for pitch differences.

While tuning adjustments sound like a routine procedure, not so fast! We all know that our own ability to discern pitch problems is only the beginning. We may know that the instrument is out-of-tune but making the call of sharp or flat can be difficult.

Sometimes the differences are exceptionally small. Students should be encouraged to experiment with changes in the embouchure and/or tuning slides. If the challenge is greater, then guess! Your chances of being correct are 50/50. Or… pull out… a lot. Now the student knows the horn is flat, and, by the way, a correctly tuned pitch is notably easier to find when approaching from beneath the pitch.

These three components become a process. Reference, Internalization, and Adjustment are a combination of activities that will lead to better listening and better results. As ensemble members become more experienced, the speed of the process will improve.

I recommend dividing the band by sections (see below) and tuning to notes that are comfortable, in the middle of the range, with notes that can reliably be tuned.

An oboe is a traditional instrument to present the reference. Its timbre is of the quality that allows it to project and be heard. Any instrument, however, that can deliver a tuner-evaluated pitch can be utilized.

| Reference Pitch | Section |

| Concert F1 1st Space Treble Clef |

Low Brass and Low Winds (Bassoons, Bass Clarinets, Tenor & Bari Saxes) |

| Concert F1 | Trumpets & Clarinets (second line G) |

| Concert A1 2nd Space Treble Clef |

Alto Saxes and Horns |

| Concert A1 | Piccolo, Flutes & Oboes |

Having fewer instrumentalists tuning assists the players to focus and compare their pitch to the reference, and ultimately adjust the instruments. Tutti tuning can be so overwhelming that hearing oneself and making adjustments is a challenge.

As a middle school, high school, and collegiate director, this author divided his ensembles as outlined above. The process was organized, and the players learned to listen and adjust accordingly.

As stated earlier, as the ensemble becomes more experienced, the speed of the process will improve. That said, it is further recommended to check pitch more often. Tuning at the beginning of a rehearsal while the room is a cooler environment is bound to change. After 20-25 minutes of rehearsal, pitch changes, too.

Going through a second or third tuning process reinforces the need to listen, recheck pitch, and makes the procedure more familiar. Don’t tune just once per day. Tune often.

Try not to fall prey to “quick and easy fixes.” As I said before… there is no secret. This is a skill that is essential, and it’s a process that develops slowly.

Every difficult practice or course of action seeks an easier method. As humans, we will spend countless dollars for shortcuts or easy mechanisms to save time, effort, or pain. We look for a new pill to help us lose weight effortlessly or for volumes of books to make us more successful, more attractive, or more popular.

With regard to intonation training, we have techniques that might “guarantee” achieving “Nirvana” with “in-tune playing.” I submit that some of these approaches are aural therapy to be used as part of the process… not as a replacement.

Electronic drones are helpful, but exorbitant volume levels can prevent students from assessing their own pitch. Small tuners which clip on the instrument are a personal tool… certainly not an ensemble device. They are great for individual practice, but they are not helpful for adjusting the pitch of chord tones.

A personal phone and a tuning application is a tool: great for checking individual pitch, but the reward of a pretty, green disk with a “smiley face” may not improve listening. It may promote a “game” of watching. We want our ears to become more discriminating, not our eyes.

In short, use therapeutic devices as a means of helping students hear better. They can certainly be helpful, but the real skill is in developing the muscle we have in our ears. There is no substitute for the “weightlifting” of intonation training.

Stick with the process:

- Present a reference pitch

- Internalize the pitch

- Adjust the instrument

- Reassess constantly

Good luck! Stay in tune!

About the Author

JOSEPH HERMANN, Director of Bands Emeritus, served at Tennessee Tech University for 28 years as Professor of Music. Hermann is sought after as a conductor, adjudicator, and speaker and has presented clinics, workshops, and has conducted around the world. His symphonic bands have been featured at national conventions; recordings of his ensembles have been issued as reference for music educators nationwide. Before his appointment at Tennessee Tech in 1989, Hermann was a director at the University of Arizona, Indiana University, and East Tennessee State University. He taught instrumental music at every educational level and supervised the Des Moines (Iowa) Catholic Instrumental Music Program.

Hermann is a member of the prestigious American Bandmasters Association, and in 2009-10, he served as its President. He is the recipient of the KKѰ Distinguished Service to Music Medal in Conducting and the TBΣ Paula Crider Outstanding Band Director awards. In 2015, Hermann was inducted into the Tennessee Bandmasters Hall of Fame. Mr. Hermann is affiliated as an Artist/Conductor/Clinician with Jupiter Band Instruments, Inc. and serves as their Senior Educational Consultant.

The content of this Blog article or Banded Story is the intellectual property of the author(s) and cannot be duplicated without the permission of KHS America and/or the author(s). Standard copyright rules apply.

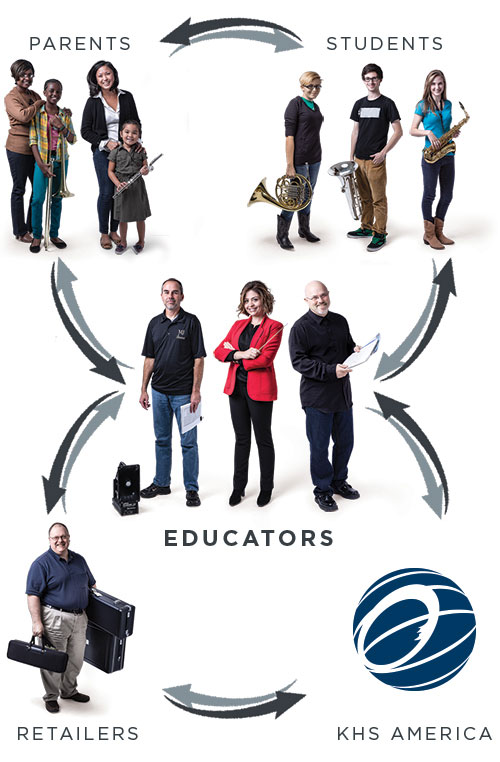

We look forward to the evolution of this exciting program, and welcome feedback on how we can further enhance the work that you do in music education.

We are excited to offer your program the opportunity to join the KHS America Academic Alliance today.

We look forward to the evolution of this exciting program, and welcome feedback on how we can further enhance the work that you do in music education.

We are excited to offer your program the opportunity to join the KHS America Academic Alliance today.