In last week’s blog, I offered some thoughts about common issues that arise when rehearsing a full orchestra. What follows are other problems that we often encounter when we combine winds, percussion, and strings into that glorious medium.

How They Produce Sound. Put simply, wind players need to breathe and string players don’t! When full orchestra music is written with overlapping, layered, or disjunct phrases, this is not a worry. But when a piece calls for long passages of lush, continuous, uninterrupted tutti playing, this common problem is obvious and creates a noticeable deficiency in the success of the performance. So often, in a work like that for full orchestra one hears the strings play with a rich, constant, seamless sound, only to hear the winds putting spaces in that same passage so they can breathe. This issue is just as noticeable with smaller forces, such as when a unison line is played by one string part and one wind part, for example, the violins and the flutes. That lack of unity is glaring and detracts from a cohesive performance. Since rarely do full orchestras have the forces for the winds to stagger breathe, we are usually left with having the string players end their phrases to match those of the winds. However we decide to solve this dilemma, remedying this concern makes all the difference in the quality of the orchestra’s performance.

Volume/Balance. When we rehearse a string orchestra, we address overall ensemble balance, as well as section balance. Likewise, when rehearsing a concert band, we attend to overall ensemble, family, and section balances. When it comes to full orchestra, we certainly need to do the same. However, beyond that, two common problems regarding volume and balance arise simply by nature of how we constitute the ensemble. When the traditional forces of a modest-sized wind and percussion section are employed with a large robust string section, the problem is that often the winds are not heard well and need to project more. But when that same wind and percussion section is playing with a modestly-small string section, the strings are often drowned out, necessitating the winds and percussion to play softer. All of that must be accomplished, while of course maintaining good balance. Very often, this problem is compounded and exacerbated when orchestras use doubled – or even more – winds in an effort to allow as many students as possible the opportunity of playing in the ensemble. As well, percussion in any scenario must maintain that perfect balance – pun intended – of knowing when to be in the foreground and when to be in the background.

Peter Loel Boonshaft, Director of Education

KHS America

The content of this Blog article or Banded Story is the intellectual property of the author(s) and cannot be duplicated without the permission of KHS America and/or the author(s). Standard copyright rules apply.

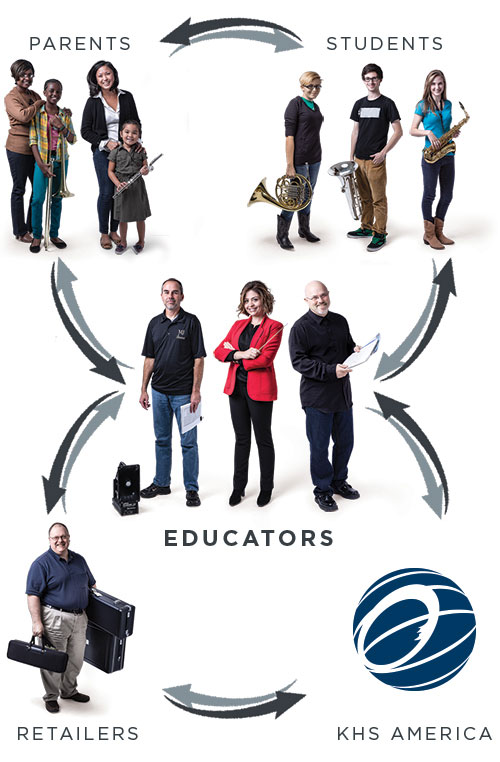

We look forward to the evolution of this exciting program, and welcome feedback on how we can further enhance the work that you do in music education.

We are excited to offer your program the opportunity to join the KHS America Academic Alliance today.

We look forward to the evolution of this exciting program, and welcome feedback on how we can further enhance the work that you do in music education.

We are excited to offer your program the opportunity to join the KHS America Academic Alliance today.