A DIFFERENT DRUMMER

By Stephanie Murphy-Lupo

Mr. Dick Cully is so intensely passionate about music, history, and patriotism:

While dating in Manhattan in the 1940s, his parents spent many an evening at the joint that was jumpin’ with big-name music talent — the Apollo Theatre in Harlem. They married, Maureen was born, and Dick arrived four years later, in 1949. The couple’s collection of Big Band records multiplied like rabbits — with Jeanette receiving an LP every Christmas, birthday and wedding anniversary.

For Dick’s first Christmas, his father gave him a Spike Jones drum set and snapped a priceless picture of it — moments before the tot put his foot through the bass drum. Within a few years, the family moved to Lyndhurst, N.J., where Dick attended Catholic school and learned the world according to the Felician Sisters. Before long, a rap on the knuckles would sound like “rat-a-tat-tat.”

The Cully household was a hub for friends who gathered around the turn-table to hear Richard’s favorites — classics such as Duke Ellington playing “Take the A-Train,” and Glenn Miller’s “In the Mood.”

During the heyday of “American Bandstand,” Dick collected rock ‘n’ roll records, soaking up the “new sounds” on his stereo. Father and son listened to the radio by the hour, fascinated with the rhythms of the classics made immortal by the likes of Sinatra and Count Basie Orchestra. Dick decided to learn to play the drums, after hearing the now-immortal soundtrack for the James Bond classic, “Goldfinger.” He was able to read music from the get-go but nearly quit after four months of lessons because of difficulty with his left hand.

In high school, Dick studied drumming techniques with Juilliard graduate James Rago, who later joined the Louisville Symphony. Within a few months, Rago said his pupil was ready for his own set of drums. Richard Sr. had a musician friend who took father and son on a tour of “Music Row” in Manhattan. Needless to say, the kid with riffs in his brain came home with visions of sugarplums dancing in his head.

Two days later, his father presented Dick with a splendid silver-sparkle set of drums with Zildjian cymbals.

Unlikely to embrace a conventional path, Dick had little interest in the high school band. Thus, his “band leader” role emerged at age 17, when he put together The Charades with two guys from school and a neighbor. The four-piece combo got their feet wet playing gigs for the Elks Lodge, the Knights of Columbus, and of course, the perennial “weekend wedding circuit.”

For about five minutes one evening in 1967, Dick considered a career in the new-fangled field of electronics — having become briefly enamored with computers. But the tug of the timpani was already too strong. Sticks would be his career, and that was that.

Rago advised him to enroll at the Berklee School of Music in Boston. Two years later — he had a firm foundation, a solid understanding of music theory, good ear training, plenty of experience in music arranging, and a boatload of disillusionment — when Berklee’s teachers wanted him to study piano and vibraphone. With thoughts of suicide and a failed plan to off himself, he was momentarily distracted by the brutal cold in Boston. He quit school, returned to Lyndhurst and called a former teacher, who introduced him to a very important musician.

Enter the great Ed Shaughnessy, drummer for Doc Severinsen’s band on “The Tonight Show.” While studying with Shaughnessy, Dick got sideman gigs with orchestras playing throughout New York and New Jersey. When Severinsen’s band and the TV show relocated to California, Cully had to cut the cord with Shaughnessy.

He had met Henry Lewis, a studio musician in New Jersey, and joined his trio in Memphis. They played dates for the Holiday Inn circuit across Tennessee and Arkansas. Four months on the road put a dent in Cully’s enthusiasm, so he went home to Lyndhurst.

In 1974, just as Cully was putting together his own eight-piece ensemble, Richard Sr. had a heart attack and began a year of recuperation. To help support the family, Cully put aside music to take a job as a shipping clerk for Mosler Safe Company. He also sold his car to help pay the bills.

His father retired in 1978 and his parents moved to Boca Raton. Cully went, too, because being near family outweighed the idea of living in what was then a cultural wasteland. He had no contacts in the music business in South Florida. Transferring his union membership to the local did little to improve his prospects. For three frustrating years, he played no music and worked at a variety of unrelated jobs.

At that time, the Boca area had a pops orchestra, a symphony and legions of trios and small combos — all going nowhere. Cully intuited a void in music offerings that would appeal to the area’s Baby Boomer and retiree demographic; so he began to build a library of arrangements for a 15-piece Big Band.

“My dad said, ‘Look, if you can’t find a band, go out and put one together yourself.’ Dad believed in me, as he always had.”

Suddenly, his world was upside down again, when his father suffered a fatal heart attack. Back in New Jersey to visit relatives that Christmas, he made a New Year’s resolution to honor his father’s wish that he pursue his dream.

That winter, a new Holiday Inn opened in Boca with a large lounge and dance floor. Cully looked around, promising himself that one day, his band would play the room.

Cully approached Dr. Bill Prince, who was Director of Jazz Studies at Florida Atlantic University. Cully became the drummer for the Community Jazz Band rehearsals and annual concert — all gratis.

Then he contacted the head of Fantasma Productions, a local rock concert promoter, and sold the guy on “The Dick Cully Big Band,” which at that time remained a mirage. Fantasma booked the band for a festival at Dreher Park Zoo — for a whopping $100, and the lure of free publicity.

Trying to corral some FAU student musicians, Cully called 30 and a handful responded. One week ’til show time, a very nervous “band leader” called Prince, gave him the playlist and asked for some names. Fifteen guys showed up, Cully handed out their uniforms — black T-shirts — and a band was born.

He paid the guys union-scale wages out of his own pocket, but worked on his plan to generate more concerts. He had made a tape of the zoo show and put together a pitch with some photos. For four months, he pestered the owner of the new Holiday Inn, finally persuading the guy to take a chance.

On Easter Sunday 1982, the Dick Cully Big Band opened in that venue, The Bounty Lounge. The joint was packed, and the owner was astonished.

That “one-night gig” ran for seven years and grew Cully a bumpy, multi-decade career as someone not well enough known to fully realize his potential. Take, for instance, Buddy Rich, one of the biggest stars of all time. The legendary stick-man known as “the world’s greatest drummer” had a unique style, other-worldly technique, custom groove, driving beat and single-stroke roll. Cully became such a talented drummer, the press started saying he was the one musician on earth who could perform certain licks like Buddy Rich.

In 1984, he was recognized as a “World Class Drummer” by drumstick manufacturer Pro-Mark Corporation of Houston, Texas. In 1989, the Dick Cully Big Band was chosen as “One of the Best Bands in the Nation” by “Down Beat magazine.” The group has been featured numerous times on “Jazz Discovery,” a TV program on the BET network.

Perhaps with even better visibility, he might have succeeded in launching a “Big Band Jazz Café” attraction in theme-happy Orlando. On the long path to not getting his way — adapting to changing times and being forced into retirement for lack of work — Cully endured knee, elbow, shoulder and back surgeries, and survived five heart attacks.

Enter the ghost of Elfego Baca, a deputy sheriff and U.S. Marshal in late 19th-century New Mexico. Walt Disney created a TV mini-series about the hero in 1958, and cast Robert Loggia in the title role. As a child, Dick and his dad watched “The Nine Lives of Elfego Baca” every Friday night.

As for Cully’s “nine lives,” he can cite eight whiffs of death: a near-fatal car crash a week before high-school graduation; attempted suicide in 1968; smoke inhalation while performing aboard the Scandinavian Sun cruise ship, after a 1984 fire killed two and injured hundreds; and five heart attacks between 1995 and 2013.

Cully acknowledges that he was incredibly young and impossibly despondent to try to take his life that year in Boston:

“I think I knew even at Berklee that music would be a hard road, and I wasn’t mature enough then to handle it.”

He considers himself just an average kid from a middle-class family who loved music. “Average,” except for having a dad who was fully engaged in being a special parent:

“He was my inspiration and No. 1 cheerleader. Music was his muse, and then it became mine. He made sure we had time for baseball, football, bowling and billiards, but I didn’t really excel at anything outside music.”

More importantly, Richard Sr. shared his wisdom, often sitting at the kitchen table while Jeanette prepared supper. On one occasion, he asked his father about a career in music:

“He said, ‘I don’t care if you want to dig ditches, be a lawyer, doctor or a musician. You’re the one who has to do it for the rest of your life. Many great people get up every morning and go to a job they hate. You have to choose what makes you happy.’ Once I made my decision, I did have second thoughts as I saw my peers — one guy going off to college, another joining the Army. If I’m going to be a musician, what do I do now?”

What he does “now” is push ahead with his belief he can help the country with “Reboot America Musically,” using the Great American Songbook to teach American history, create jobs for musicians, boost the economy and remind Americans we are supposed to be “a grateful nation,” mindful of military sacrifices.

“When I do get my hour of fame, it will be for a program with all the ingredients to change lives”

The content of this Blog article or Banded Story is the intellectual property of the author(s) and cannot be duplicated without the permission of KHS America and/or the author(s). Standard copyright rules apply.

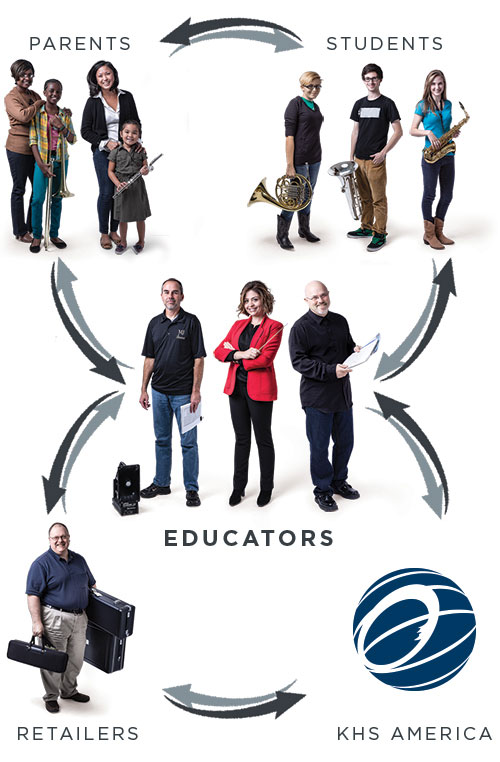

We look forward to the evolution of this exciting program, and welcome feedback on how we can further enhance the work that you do in music education.

We are excited to offer your program the opportunity to join the KHS America Academic Alliance today.

We look forward to the evolution of this exciting program, and welcome feedback on how we can further enhance the work that you do in music education.

We are excited to offer your program the opportunity to join the KHS America Academic Alliance today.