While there are exceptions, most wind players still live on the same basic embouchure setup: flat chin and firm corners. Those are the two most visible, consistent markers across wind instruments. In an ensemble setting—especially in programs where many kids don’t have private lessons—directors can help students a lot by watching and reinforcing these two fundamentals.

When it comes to embouchure or mouthpiece decisions, I always start with one question: “Do they make a characteristic sound, and can they move around the instrument?” If the answer is yes, don’t touch it. There are real exceptions in brass playing, and plenty of students have quit because an embouchure or mouthpiece issue was either over-diagnosed or missed entirely. Most low brass “embouchure problems” are fixable with attention to vibration, air, visible setup issues, and sensible equipment choices. Directors who focus on what they can fix quickly tend to create healthier players who still enjoy playing after they graduate.

If you teach beginners and then don’t keep reinforcing embouchure fundamentals year after year, physical growth can quietly change things. For low brass and horn students, as they get taller the mouthpiece can drift lower without anyone noticing—until range drops or tone starts to fall apart. You’ll see it with habits like resting a trombone on the shoulder, setting euphonium/baritone on a chair or lap, horn players resting the bell on the leg, or tubas being held like they were when the student was three inches shorter. As the student grows, the horn angle and holding position must change. A lot of this happens over the summer, and when summer band hits, the face gets worked hard and a “new normal” can set in before anyone realizes it.

That’s why constant reminders on how to form the embouchure matter, and why directors need a way to explain it in a group setting. A couple of tricks I’ve used: start by forming the letter “M,” then firm the corners while using an index finger to stretch and pull the chin down and away from the upper lip—keeping the lips together. Another approach is to take a paper clip, place it at the point of the aperture, and try to hold it parallel to the floor while also stretching the chin down and firming the corners.

Before changing equipment or diagnosing a “bad embouchure,” use this checklist:

- Mouthpiece placement: centered left–right and consistent day to day. Avoid dramatic shifts in search of range.

- Firm corners, not a pinched center: too much rim pressure often kills vibration consistency.

- Neutral jaw: not aggressively forward or pulled back.

- Air and release: silent, quick breath; then release air into the note. No grunting or squeezing.

- Response test: middle-register entrance at mp. If it speaks cleanly at a soft volume, the setup is usually sound.

If a student can only start notes loudly, you’re usually looking at a coordination/pressure issue—not a mouthpiece size problem. The best brass players look boring because they’re consistent while their sound and range grow steadily. Keep the emphasis on minimal, efficient adjustments. Short-term success by clamping or pressing always costs you long-term stability—swelling, inconsistency, loss of clarity, and unreliable response.

Phrases like, “Keep the center responsive—let the air do the work,” reinforce healthy habits. Treat pressure as a symptom. Lingering rim marks, swelling, a spreading tone, and fast fatigue usually point to too much pressure.

A Five-Minute Daily Embouchure Builder

This routine can be used in sectionals or assigned independently without eating rehearsal time:

- Breath + soft attacks (1 minute): 8–10 middle-register notes at mp–p, focusing on immediate response.

- Easy slurs (2 minutes): simple lip slurs in comfortable positions; moderate dynamics; steady tone.

- Gliss-connected long tones (1 minute): on mouthpiece, or on leadpipe with tuning slide removed for valved instruments—small, controlled movement to keep the face alive, not locked.

- Range check without strain (1 minute): 2–3 notes above and below comfortable range. Stop before force appears.

Phrases to use: “Reset—softer, center the sound, corners firm.” “Same face, better air.” “If it takes force, it’s not the solution.”

Mouthpieces

Smaller students sometimes get put on larger mouthpieces to try to match the sound of bigger students. A one-size-fits-all approach has become common. But tonal consistency isn’t achieved by everyone playing the same mouthpiece and horn. That’s like making every kid in marching band wear a size 14 shoe so everybody matches.

Mouthpiece selection should start with lip size, mouth width, and tooth structure. Larger rim diameters often work well for students who play more top lip in the mouthpiece and/or have wider lips with gapped teeth. Smaller rim diameters often work better for students who play a more even distribution of top and bottom lip, or who have thinner lips, a narrower mouth, and non-gapped teeth. There are exceptions, but this is a good starting point.

When it comes to numbering systems, most are based on Vincent Bach and Renold Schilke. KHS uses the Bach standard. Bach sizes are usually a number and letter: larger rim diameter = smaller number, and cup depth is indicated by letter (C is shallow for low brass; G is deeper). In the Schilke system, larger number = larger rim diameter. If there’s a letter, cup depth runs from A (shallow) to E (deep). If there’s no letter, it’s a standard balanced shape. Quick reference: a Schilke 51 is like a Bach 5G, and a Schilke 52D is like a Bach 4G.

The larger the rim diameter, the more strength it usually takes to play consistently. The deeper the cup, the more the upper register tends to run flat. Deepening a cup to “get a better sound” can be a quick fix with long-term consequences. Comfort and embouchure stability should drive the mouthpiece choice—not “what the pros play.”

In closing, the goal isn’t to create a picture-perfect embouchure; it’s to build a healthy one that lasts. Students tend to quit when the fix becomes bigger than the music, or when they start to feel like something is “wrong” with them. A director who checks the basics, teaches the body to respond, and avoids unnecessary equipment changes protects both the player and the program.

Originally from Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, TOM MENSCH is the Artistic Director of the East Texas Youth Orchestra in Tyler, Texas and the adjunct Trombone Instructor assisting Dr. Deb Scott at Stephen F. Austin State University. Previously, he was the Director of Bands at Whitehouse Independent School District and also the Fine Arts and Communications Learning Leader for WHITEHOUSE HIGH SCHOOL and before that, the Director of Bands and Professor of Trombone at Tyler Junior College. Tom has conducted numerous low brass and band clinics throughout North East Texas and has been the clinician for several TMEA/ATSSB Region 3, 4 and 21 concert bands as well as the Four States Honor Concert Band. He is an artist for XO Brass Instruments, a member of the KHS American Instrument Brand and he has helped in the development of trombones within the XO trombone line of instruments. He is also an artist Greg Black Mouthpieces. Mr. Mensch is an active performer on tenor trombone with the Rose City Brass Quintet, Lead Trombone with the Souled Out Jazz Orchestra, The Metro Big Band, is the Principal Trombonist with the Longview Symphony, and is a freelance musician throughout the East Texas Area. He was a featured soloist with several high school bands and colleges and has performed as a soloist at the Texas Music Educator’s Association Conference. As a member of the Metro Big Band, he has performed in over twelve different countries and recorded 7 albums. He earned his Bachelor of Science in Music Education from the Pennsylvania State University in 1996 and earned his Master’s Degree in Trombone Performance from Stephen F. Austin State University in 2009. Tom is a member of the Texas Music Educators Association, International Trombone Association, The National Band Association, Texas Bandmasters Association, Phi Beta Mu, and Phi Mu Alpha. He is happily married to Heather, who is also a professional bass trombonist and the Department Chair of Music at Tyler Junior College, and they have a dog named Zoe.

The content of this Blog article or Banded Story is the intellectual property of the author(s) and cannot be duplicated without the permission of KHS America and/or the author(s). Standard copyright rules apply.

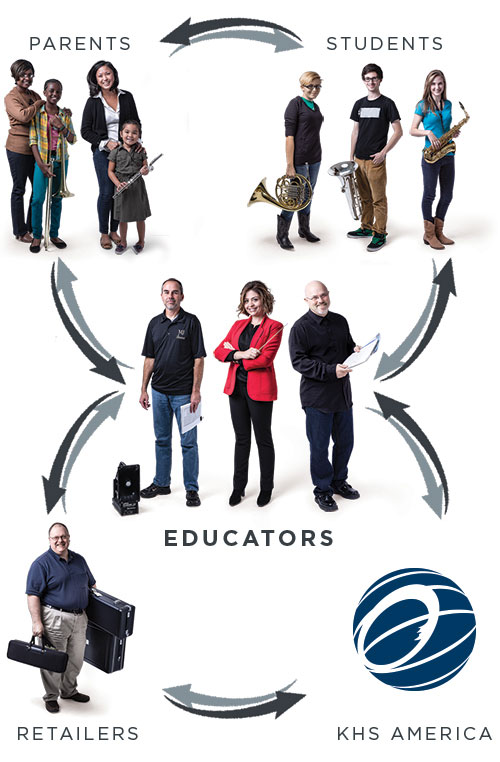

We look forward to the evolution of this exciting program, and welcome feedback on how we can further enhance the work that you do in music education.

We are excited to offer your program the opportunity to join the KHS America Academic Alliance today.

We look forward to the evolution of this exciting program, and welcome feedback on how we can further enhance the work that you do in music education.

We are excited to offer your program the opportunity to join the KHS America Academic Alliance today.